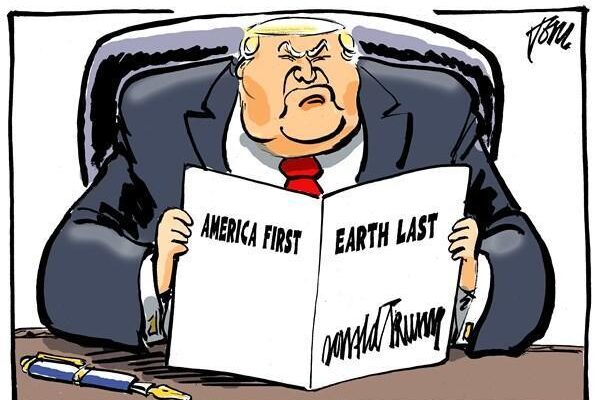

The atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide have increased to levels unprecedented in at least the last 800.000 years. Carbon dioxide concentrations have increased by 40% since pre-industrial times, primarily from fossil fuel emissions and secondarily from emissions from land use change1Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)(2013)Climate Change 2013: Physical Science Basis. Working Group 1 Contribution to the fifth assessment report on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide have increased to levels unprecedented in at least the last 800.000 years. Carbon dioxide concentrations have increased by 40% since pre-industrial times, primarily from fossil fuel emissions and secondarily from emissions from land use change1Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)(2013)Climate Change 2013: Physical Science Basis. Working Group 1 Contribution to the fifth assessment report on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

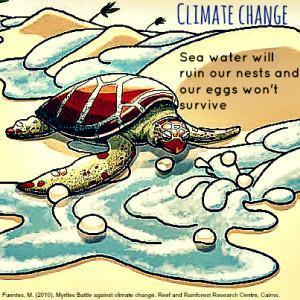

Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and since the 1950s, many of the observed climate changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The atmosphere and oceans have warmed, the amounts of snow and ice have diminished, sea level has risen and the concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased. The oceans have absorbed about 30% of the emitted anthropogenic carbon dioxide, causing ocean acidification2IPCC as above.

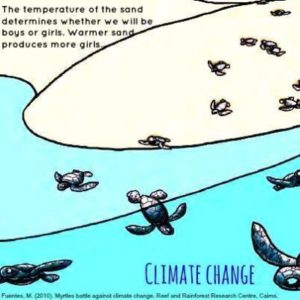

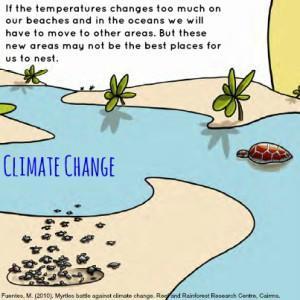

Sea turtles already face significant threats that challenge their survival (incidental captures during fishing, degradation of nesting areas, maritime traffic, marine pollution and especially plastic litter, illegal trade and consumption etc.). Climate change places sea turtles under threat that we cannot fully estimate (see EuroTurtle for more information).